Q&A with Steen Hartsen, Faculty & Forensic Analyst

“We are proud to continue making advances and helping to close cases as we conduct this important humanitarian work.” – Steen Hartsen

BCIT’s Forensic DNA Laboratory is equipped with the latest technology for human identification, and is the only academic forensic laboratory accredited by the Standards Council of Canada to the same level as the RCMP National Laboratory. Our team provides expert services on challenging cases for local, national, and international coroner and police agencies.

Forensic Investigative Genetic Genealogy (IGG or FIGG) has become one of the most powerful tools used in forensics since it burst into the limelight with the successful identification of the golden state killer – a long-cold California case – in 2018. BCIT’s forensic science experts are frequently asked to explain the uses, advances, and limitations of new forensic technologies and approaches as cases come into the media spotlight.

In this blog, BCIT Forensics faculty Steen Hartsen walks us through the steps taken at the BCIT Forensic DNA Lab to investigate unidentified human remains and find a match using genealogical investigation techniques.

Q: Can you tell us how the team from the BCIT DNA lab gets involved in a case like this?

Steen Hartsen (SH): This case, and others like it, have often lingered unsolved for years. Investigators have run out of leads in trying to match a DNA sample because the deceased has not been reported missing and no other matches have come up.

When using DNA to identify human remains, you always need something to compare your profile to. But in a lot of cases family members aren’t in these databases, and remains are found with no clues as to who they may be. This is where IGG comes into play. It can provide new points of comparison that have not been available to us before.

Did you know? BCIT’s Dr. Dean Hildebrand developed and managed the BC Coroners Service’s Special Identification Unit’s first unidentified human remains and missing persons DNA database, which was pivotal in solving many cases.

The BCIT Forensic DNA Laboratory has been using genetic genealogy on these types of cases since 2022. We have recently validated a completely in-house workflow that allows us to generate the data needed to do IGG, from receiving the DNA sample to making a match.

Q: What can you share about this particular cold case?

SH: This recent case involved an individual who was found in a tent encampment in Vancouver back in January 2017, though they were believed to have died the previous year. Unfortunately, after going through his camp site, investigators were not able to find anything that could put a name to him.

He was a small man who always wore a toque and had a fondness for jalapeno-flavoured Cheetos, and was reportedly between forty and seventy years old at death. His remains were already skeletonized by the time he was found.

Q: What investigative work was originally conducted in the DNA lab?

SH: Our team processed and analyzed a piece of bone to develop a DNA profile. We then compared it to the BC Coroner’s Service missing persons database, as well as Canada’s national missing persons database. But no hits came back for this individual that would help us connect to any family members, so these standard analyses didn’t help us get closer to an identification.

The case lay dormant for six years until we were recently able to use IGG to successfully make the identification.

Q: How did Investigative Genetic Genealogy help solve this case?

SH: In 2023 we started the IGG work on this case. We were able to get data that could be uploaded to publicly-accessible databases – GEDmatch and FTDNA. These two databases are used to make IGG comparisons.

They operate a lot like Ancestry.com, where profiles are compared to everyone in the database. Then genealogists take a closer look at any genetic matches to try and see where they may fit in a family tree.

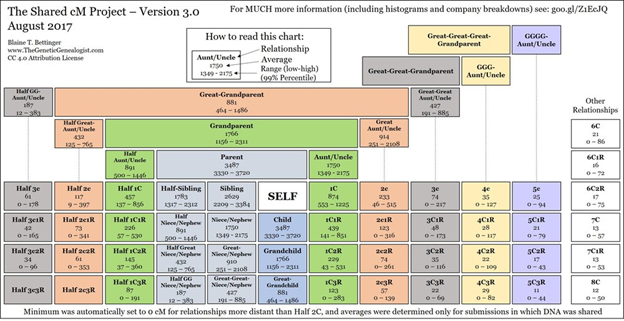

For this case, the closest match was a single person in the first to second cousin range, two matches in a second to third cousin range, and 15 matches that were third cousin or more distantly related.

This is actually a pretty good outcome – often we only get matches in the third cousin or higher range. So this kind of result is really helpful.

The chart below shows how distantly related these relationships might be. A third cousin is someone you share a great-great-grandparent with. Before genetic genealogy, we generally wouldn’t try to identify anyone unless we had someone at the sibling or parent relationship level.

Q: Having confirmed connections to relatives through IGG, what happens next to make the identification?

SH: Many forensic and technical professionals are involved in these types of complex investigations.

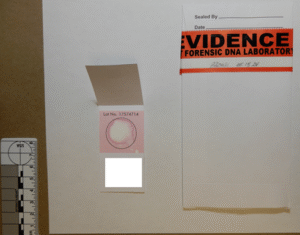

In this case, our Genealogist, Marie Palmer, was able to use this information to build up a family tree using publicly available information. She succeeded in finding a possible sister to the person we were trying to identify. The sister was then contacted by police, and she agreed to provide a cheek swab DNA sample that we could compare to the DNA we had already tested from the femur.

Using this information, we were able to make very strong association to the sibling, and thus help the coroner make a final decision on the identity of the deceased.

This person was estranged from his family and had not been reported missing; without using IGG, his remains would probably never been identified.

Q: What’s next for the BCIT Forensic DNA Lab?

SH: Due to our successful genetic genealogy pilot projects, we are now using this type of approach more widely.

And we’re pleased to say that the BCIT Forensic DNA Laboratory is now the only accredited commercial lab in Canada to offer Genetic Genealogy testing under our scope of accreditation.

We are proud to continue making advances and helping to close cases as we conduct this important humanitarian work.

Sign up for the twice-yearly Forensics Investigator and keep up with the latest from BCIT Forensics

[Feature photo: Steen Hartsen and Georgina Lush in the BCIT DNA Lab, photo by Scott McAlpine]